Rob Hornstra (born in Borne, the Netherlands, 1975) is a photographer and self-publisher of slow-form documentary work. Since graduating from the Utrecht Art School in 2004, he has worked primarily on his own long-term projects. He has published several of these projects as books. In 2012, he won first prize in the World Press Photo Award competition.

Together with the writer and filmmaker Arnold van Bruggen, in 2009 Hornstra started the Sochi Project. The project culminated in the retrospective book An Atlas of War and Tourism in the Caucasus published by Aperture in 2013, and since 2014 an exhibition that toured Europe, America and Canada.

In addition to his work as photographer, he is founder and former artistic director of the documentary photography organization FOTODOK in Utrecht and head of the Photography department at the Royal Academy of Arts in The Hague. Rob Hornstra is represented by Flatland Gallery, Amsterdam/Paris.

Argayash, RUSSIA, 2003 – Porait of war veteran Rachimov Bazhayevich in his appartment in the village Argayash..© ROB HORNSTRA

– How did you get into photography?

I have been interested in photography since I was a kid. I think I had my first photo published in the regional newspaper when I was 14 (sport section). I wanted to study photography at the Royal Academy of Art in The Hague when I was 18, but my parents thought I first had to learn a real job. I studied social and legal services, worked for a while as probation officer and afterwards still decided to do the art academy. My interest in photography is storytelling.

– Where do you get your creative inspiration from?

Best inspiration is the world around us. I am also inspired by reading newspapers, magazines, (photo)books, visiting museums and watching documentary movies. There are so many projects done by photographers, which inspire me, it is in a way unfair to only mention a few. Rafal Milach, Donald Weber, Laia Abril, Jan Rosseel, Carlos Spottorno, Jo Metson Scott, Alec Soth, Paolo Woods, Jim Goldberg…

– What is it like being a documentary photographer this days?

I believe we are currently living in a fantastic era for visual storytellers with many new opportunities in presenting your work and reaching new audiences. We are liberated from the rigid formats of traditional media like newspapers and magazines, not only in form, but also in the topics we choose. There is so much freedom now. In fact we can do and make what ever we want and that’s pure richness.

– What is your most memorable story in photography?

The Sochi Project: An Atlas of War and Tourism in the Caucasus (book is temporarily sold out, but second revised edition coming soon)

– Which series/project was most challenging for you so far?

The Secret History of Khava Gaisanova and the North Caucasus about the North Caucasus.

– What do you do besides photography?

Head of the Photography department at the Royal Academy of Art in The Hague.

– What is your favourite photography book?

Changing all the time, but for now: Jo Metson Scott: The Grey Line.

– What are your future plans with photography?

I am working on a project about my hometown Utrecht, more specifically about my neighbor who drowned two years ago in the Utrecht canal. I am mapping the social network around him. The project will be published in two parts and I plan to publish the first part early 2016.

More details at borotov.com and thesochiproject.org

Chelyabinsk, RUSLAND, 2003 – Elfrem and Sveta near a lake in Chelyabinsk, close to the Kurchatov monument, a place where alternative people gather in Chelyabinsk.?© ROB HORNSTRA

Chelyabinsk, RUSSIA, 2003 – Porait of Alexandra Alexeyevna Artamonova in the museum of the tank/tractor factory in Chelyabinsk. During the Second World War Chelyabinsk accomodated the largest tank factory in the world. Because the men in those years were all sent to the front line to fight, manufacturing was taken over by women. Alexandra Artamonova was one of those women. After the war the factory was partly transformed into a tractor plant and Aleksandra Artamonova kept on working there. Although she could have retired after 50 years of service she prefered to keep working as she loved her work so much. The factory was her life. After sixty years of faithful service she finally retired, but she misses the time she was still employed there.

Chelyabinsk, RUSSIA, 2003 – Wall with decorated veterans in the museum of the Tractor factory where they produced tanks during WWII (The Great Patriotic War 1941 – 1945)..© ROB HORNSTRA

Stokkseyri, ICELAND, ,2005 – Karl Magnús Björnsson in Stokkseyri, outside the rehearsal space of the band Nilfisk.

Utrecht, NEDERLAND, 2006 – Kid op de rand van zijn bed in de Utrechtse volkswijk Ondiep..© ROB HORNSTRA / +31 6 14365936..Utrecht, NETHERLANDS, 2006 – Kid sitting on his bed in his house in the working-class neighbourhood Ondiep in the city of Utrecht..© ROB HORNSTRA

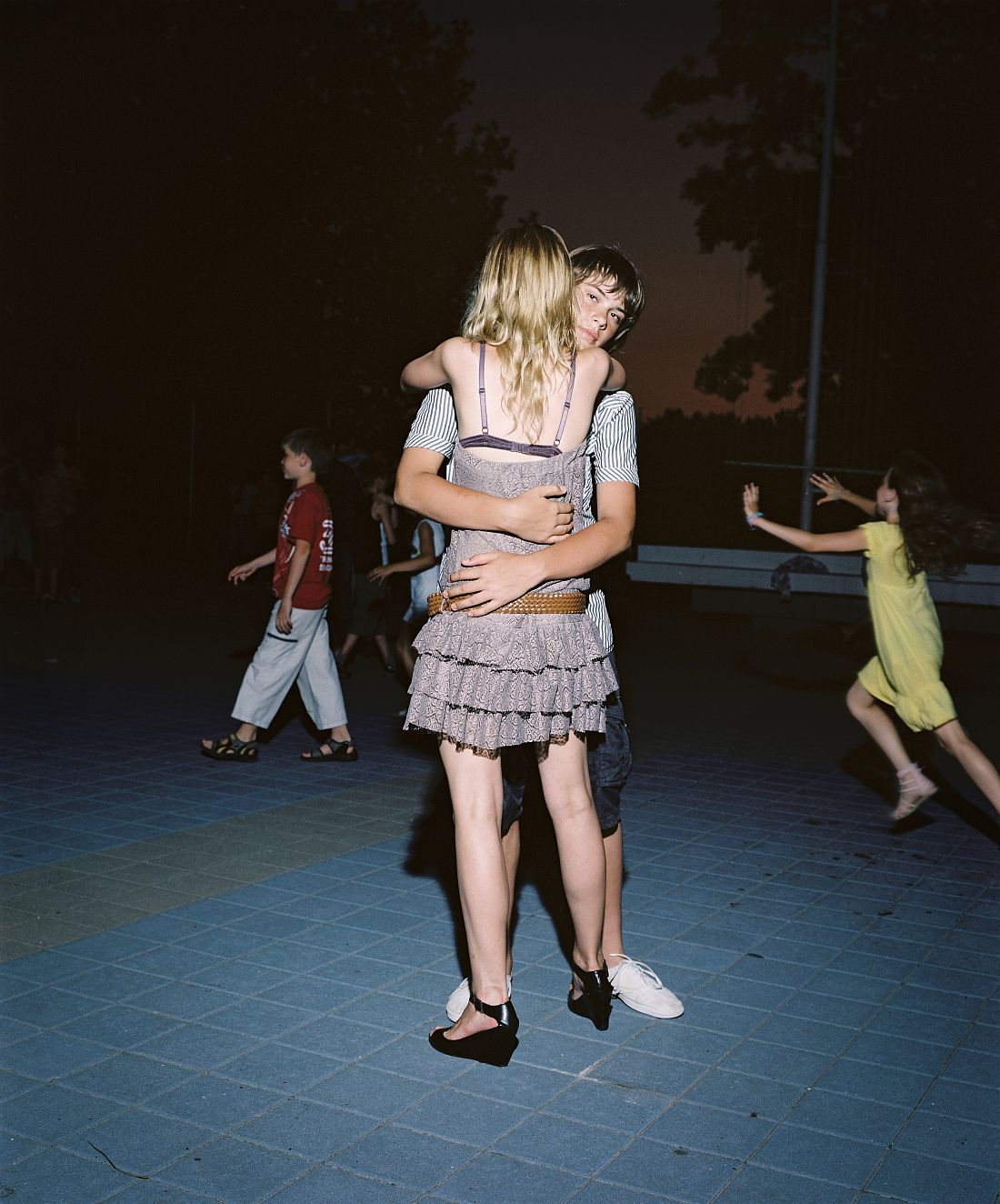

In the centre of Angarsk they call Cement Town a ‘no-go’ area. ‘Nothing more than junkies and shiv artists!’ they say of the suburb’s residents. If a fight is reported, the police do not attend to it. Everyone advises us not to go there, particularly at the weekend when there is a disco in the cultural centre. We take the warnings to heart and find a trio of bodyguards willing to accompany us on an evening out in Cement Town. Leading the group is Dmitri, a police officer who would later style himself as “the Brain”. He calls his colleague Valeri “the Eyes” and the ex-soldier Slava is “the Pitbull”. Before we go in, we drain a bottle of vodka at the edge of the village. On the boot of the car, Valeri slices pieces of bread and bacon and Slava shows us films on his mobile which he recorded himself during his tour of duty in Chechnya. Our bodyguards are small but sturdy fellows. They instruct us that if things turn nasty, we should make our escape as quickly as possible in the car. They will handle the rest. Once we are inside the cultural centre, such a scenario seems unlikely; a few giggly teenagers hang around the entrance and on the dance floor everything looks amicable. Most of the crowd is made up of girls and they are busy dancing. It’s almost a disappointment. Perhaps the bandits will turn up later?

Utrecht, NEDERLAND, 2008 – Kid belt zijn moeder vanuit zijn slaapkamer in de Utrechtse volkswijk Ondiep. Omdat hij zelf nooit beltegoed heeft, is hij afhankelijk van de telefoons van zijn buren. Niet zelden staat hij direct nadat hij is opgestaan en vrijwel alleen gewikkeld in een deken bij hen voor de deur om te vragen of hij even mag bellen..© ROB HORNSTRA / +31 6 14365936..Utrecht, NETHERLANDS, 2008 – .© ROB HORNSTRA

Andrei sits on the edge of a narrow bed. Sitting causes him obvious pain. He is from the first generation of young people who, in the middle of the 1990s, started using drugs en masse. His sister is also an addict and she also has Aids. The boy who just opened the door is her son, Andrei’s nephew. The house is a gathering place for drug addicts. In exchange for a few daily fixes, Andrei’s buddies are allowed to use the flat. Andrei is suffering from an open form of resistant TB. Just to be safe, we put on surgical masks. Lena doesn’t, as a form of respect. She’s known Andrei since she was a child. She asks him how he is and then leaves us alone. She has to go back to the street. Six weeks after our visit we call Lena to find out how Andrei is. We are just too late; Andrei died two days earlier. Andrei deteriorated rapidly. They let him lie for increasingly long periods, always on his least painful hip, with his face to the wall, as he slipped away in a feverish sleep. He continued using right up to the very end, even though injecting became harder and harder. They just put the needle in his wasted upper arm. This whole time no doctor had paid a visit. One day, Andrei’s hand hung limply over the edge of the bed. Through Lena they called a nurse. She told them: ‘Just call an ambulance,’ and they had carried him out of the flat and driven him to the tuberculosis clinic. The next morning Andrei was dead.

Kuabchara, ABKHAZIA, 2009 – Brothers Zashrikwa (17) and Edrese (14) pose proudly with a Kalashnikov on the sofa in their aunt and uncle’s house. They live in the Kodori Valley, a remote mountainous region on the border between Abkhazia and Georgia. In August 2008, Abkhazia gained control of the officially demilitarised Kodori Valley. The valley’s 2,000 Georgian inhabitants fled over the border. A few families refused to be driven out: ‘We are mountain people. Borders don’t mean very much to us. But if I had to choose between a Georgian and an Abkhazian passport, I would choose a Georgian one.’ © ROB HORNSTRA/+31 6 14365936

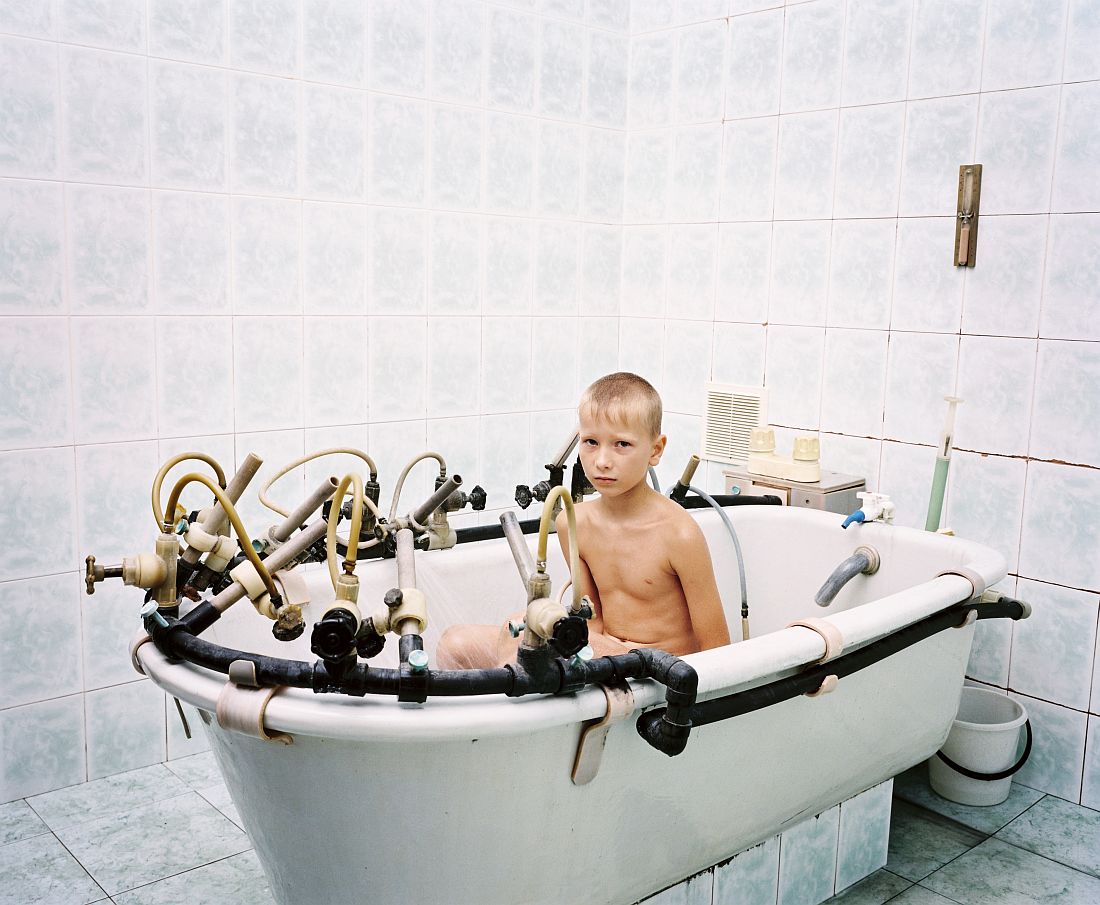

Sochi, RUSSIA, 2009 – Every year, Mikhail Pavelivich Karabelnikov (77) from Novokuznetsk travels around 3,000 kilometres in order to be able to take his holiday in Sochi. The coastal strip on the Black Sea around the subtropical resort of Sochi (Russia) has for decades been famous for its sanatoria. During the Soviet era, millions of workers were sent to one of these sanatoria annually to revive their spirits and strengthen their bodies. Today, the sanatoria are still fully booked year round mostly with elderly or disabled Russians. In the run-up to the Olympic Winter Games in 2014, almost all the sanatoria will be converted into luxury hotels. There is no place for sentimentality when it comes to the past. Sanatorium is an ode to these Soviet strongholds, revealing a deep-seated love for spas that is firmly embedded in the Russian soul. © Rob Hornstra/INSTITUTE

Matsesta, RUSSIA, 2009 – Dima is holding his leg under sulphite water from the Matsesta spa. A few years ago his leg was burned by an accident.

Matsesta has been a spa since 1902. The Matsesta water, containing plenty of hydrogen sulphide, has unique medical properties. Matsesta baths heal a lot of diseases. © ROB HORNSTRA/+31 6 14365936

Krasnaya Polyana, RUSSIA, 2010 – The second time we visit Genadi Ivanovich Kuk (82) in his tiny little house on the border of the village. Krasnaya Polyana will be the central place in the mountains near Sochi where all the ski related sports are scheduled during the Olympic Games of 2014. Genadi is frustrated by the large scale development of his small village. He is sad about the damage to historical monuments and nature.

© ROB HORNSTRA/+31 6 14365936

Utrecht, NETHERLANDS, 2010 – Portrait of my neighbors Willem & Kid in the Utrecht working-class neighbourhood Ondiep. I will continue to follow my neighbours Willem & Kid until we are all forced to leave as a result of housing development plans.

Utrecht, NETHERLANDS, 2010 – Portrait of my neighbors Willem & Kid in the Utrecht working-class neighbourhood Ondiep. I will continue to follow my neighbours Willem & Kid until we are all forced to leave as a result of housing development plans.

Orlyonok, RUSSIA, 2011 – Orlyonok was one of the main Soviet Young Pioneer camps and is currently the main Children’s Center in Russia. During the last night of the three-week stay at Orlyonok’s summer camp there is farewell party. Relations were established between children who did not know each other three weeks before. The next morning they all leave to their home cities, thousands kilometres away from each other again.

Orlyonok, RUSSIA, 2011 – Dimitri at Orlyonok’s 51st anniversary, celebrated with a flag parade, a flourish of trumpets and a touching speech by a small, cheeky kid with the intonation of a Soviet propaganda film. Orlyonok was one of the main Soviet Young Pioneer camps and is currently the main Children’s Center in Russia.

Gimry, RUSSIA, 2012 – View from the road between Shamilkala and Gimry. In the distance are the first houses of Gimry, birthplace of the 19th-century resistance hero Imam Shamil and a h otbed for the current Islamic-inspired separatism. Gimry is under a permanent KTO regime (KTO stands for counterterrorist operation), a kind of state of emergency that gives the police sweeping powers.

Karabulak, RUSSIA, 2012 – Hamzad Ivloev (44) was a policeman in Karabulak. At night he guarded a checkpoint. That was until they were attacked by the rebels ‘from the woods’, the armed groups determined to establish an Islamic emirate in the North Caucasus. Together with his friend and colleague, he was able to chase the rebels away, but on his return to the checkpoint he discovered a booby trap: a grenade had been lodged in a glass in such a way that the slightest movement would have set it off. At that moment reinforcements arrived. Hamzad started screaming and telling them to run away. But no one responded. He decided to throw himself on the grenade. Hamzad is now bedridden. He has lost his legs, his right arm and his sight. His mind is as sharp as it always was, however. ?I listen to the radio and talk to my children,? he says. But mostly he goes over and over that fatal night. ?If my colleagues had just responded, but they didn’t do anything. In retrospect, it was all for nothing. I sacrificed myself for a bunch of cowards,? he says bitterly. © ROB HORNSTRA / +31 6 14365936