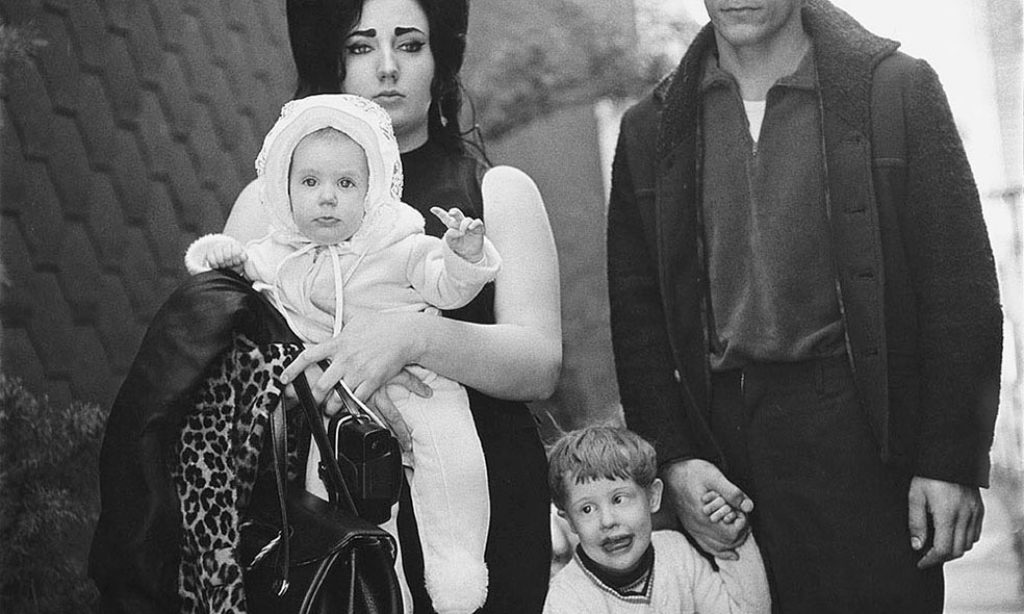

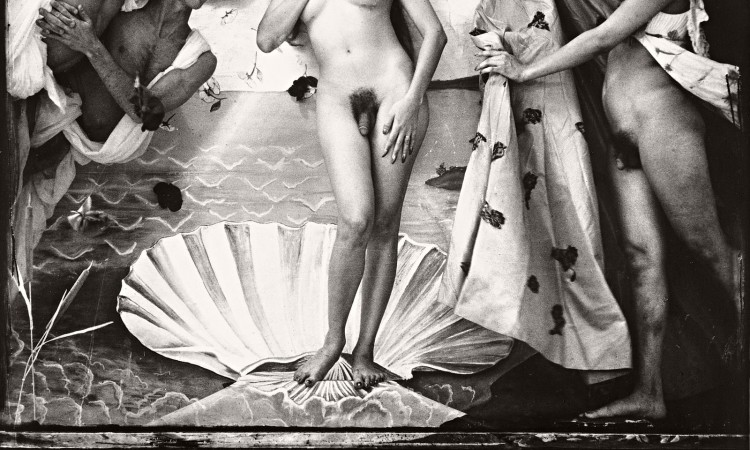

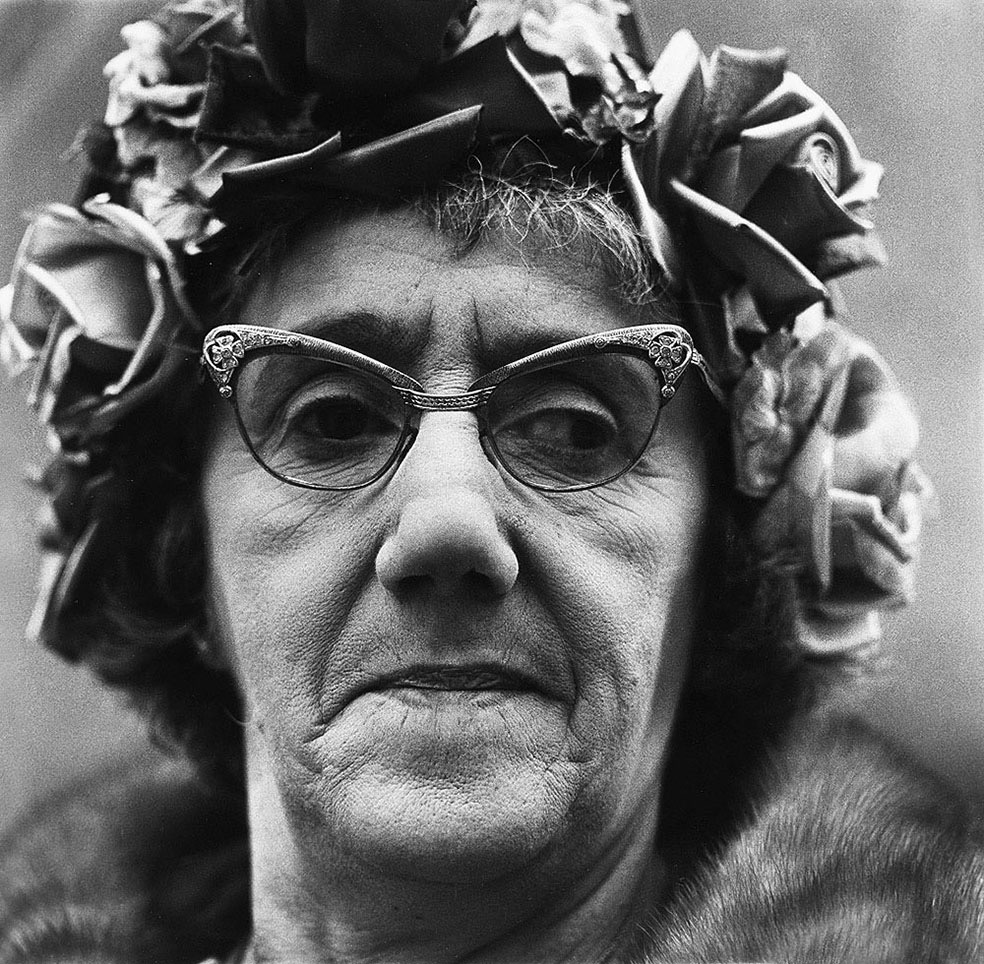

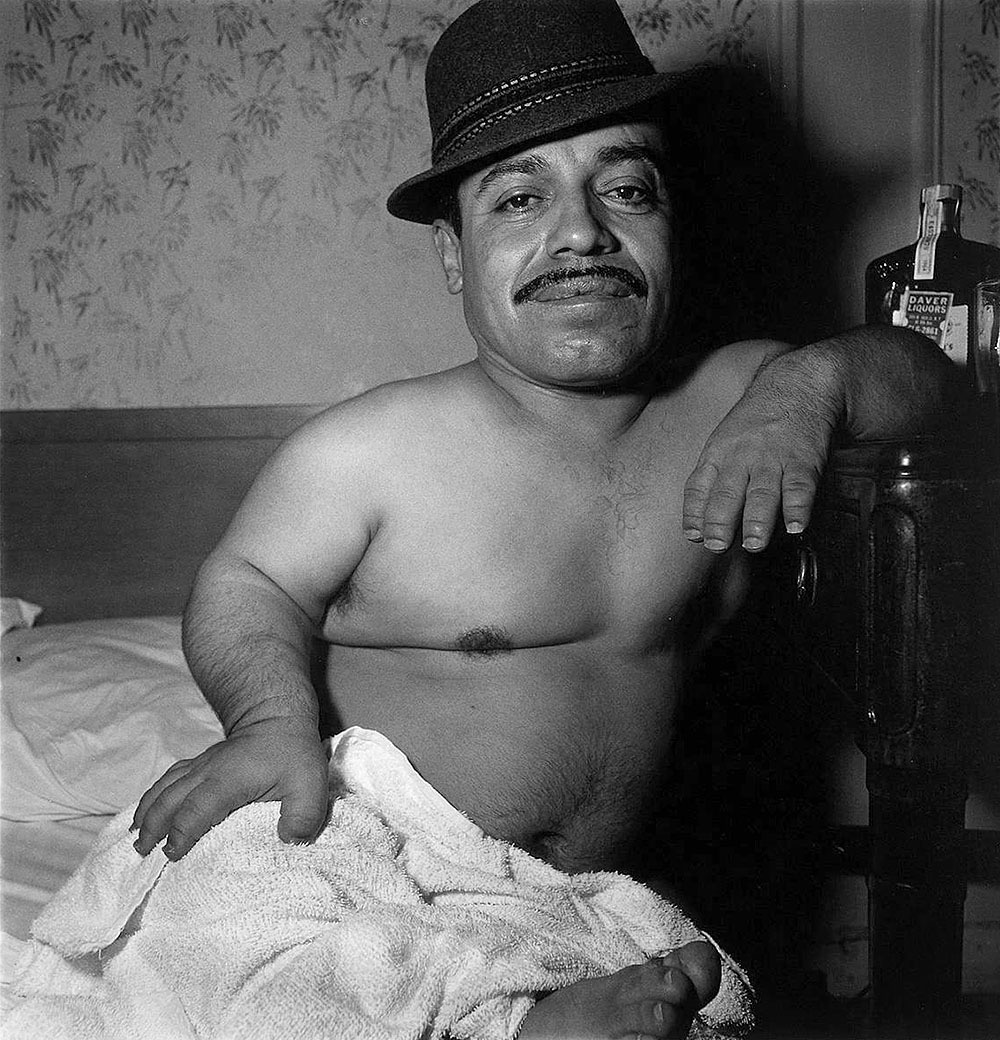

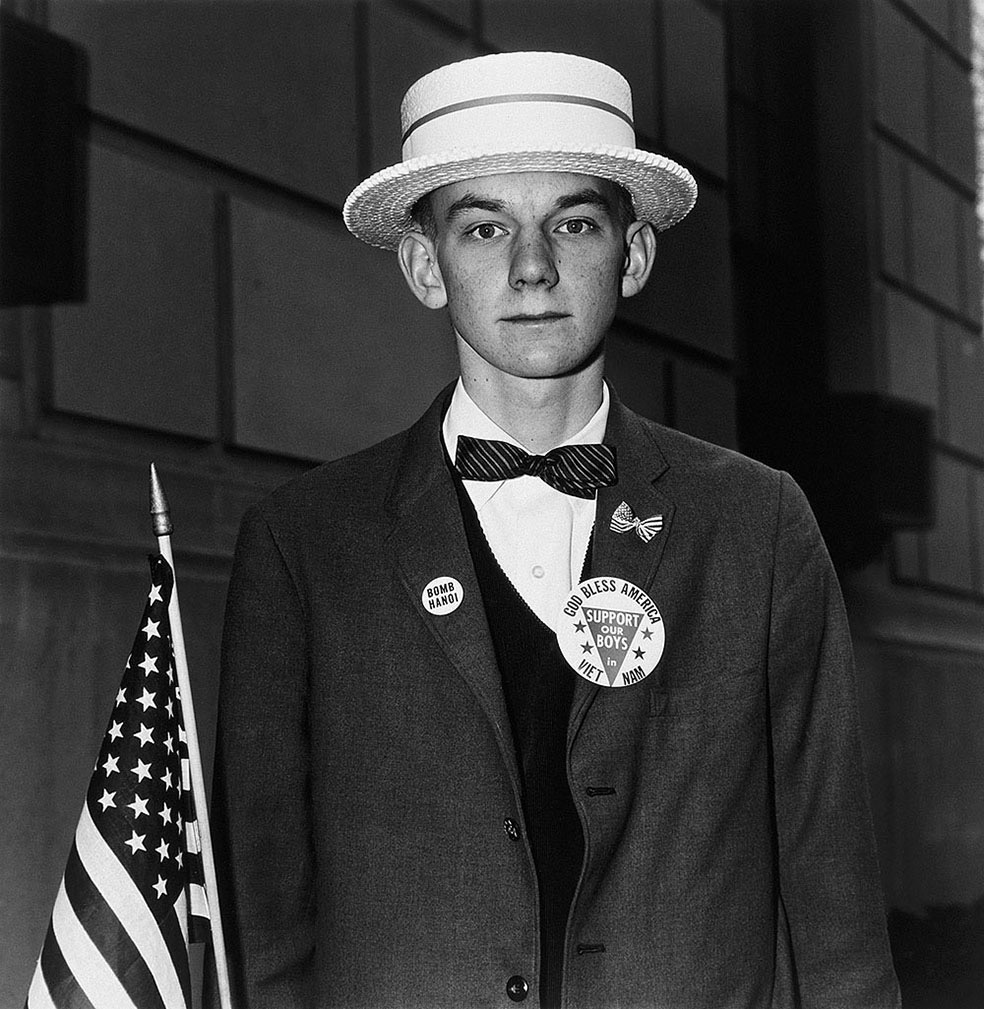

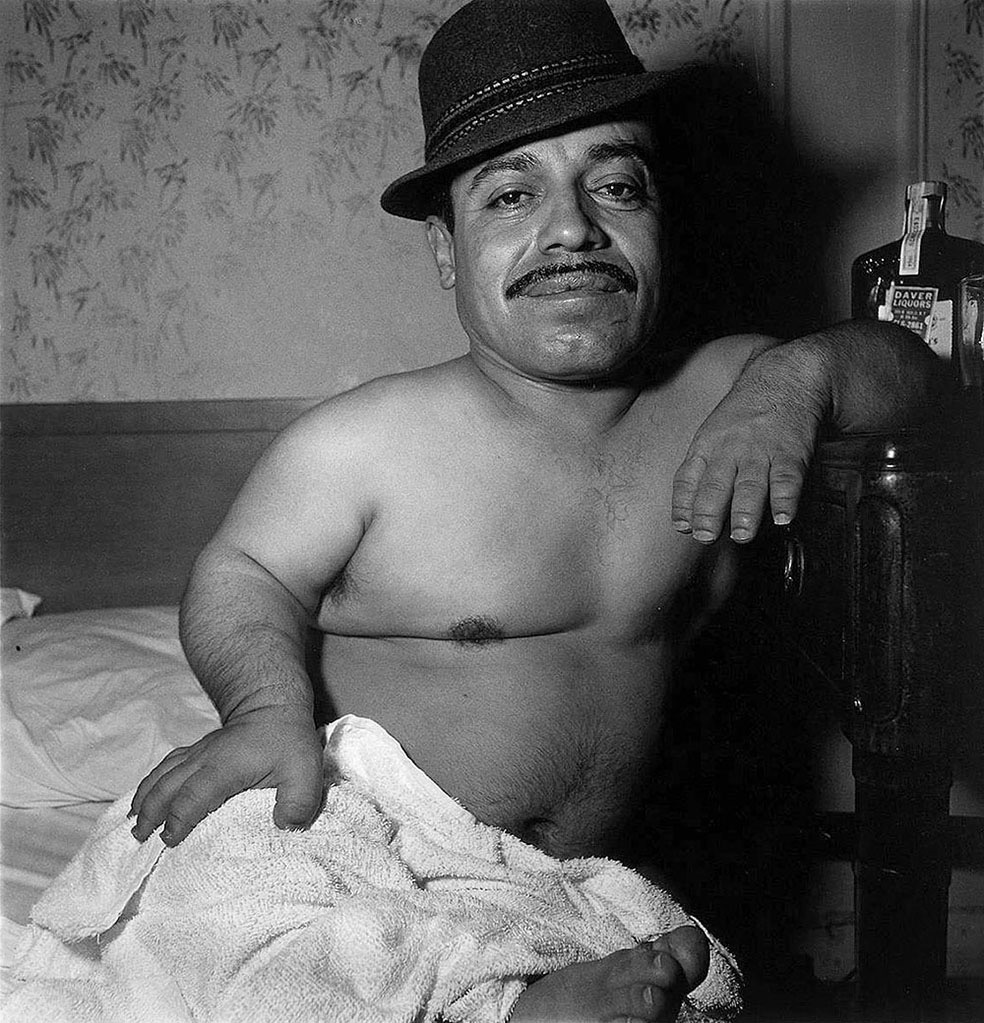

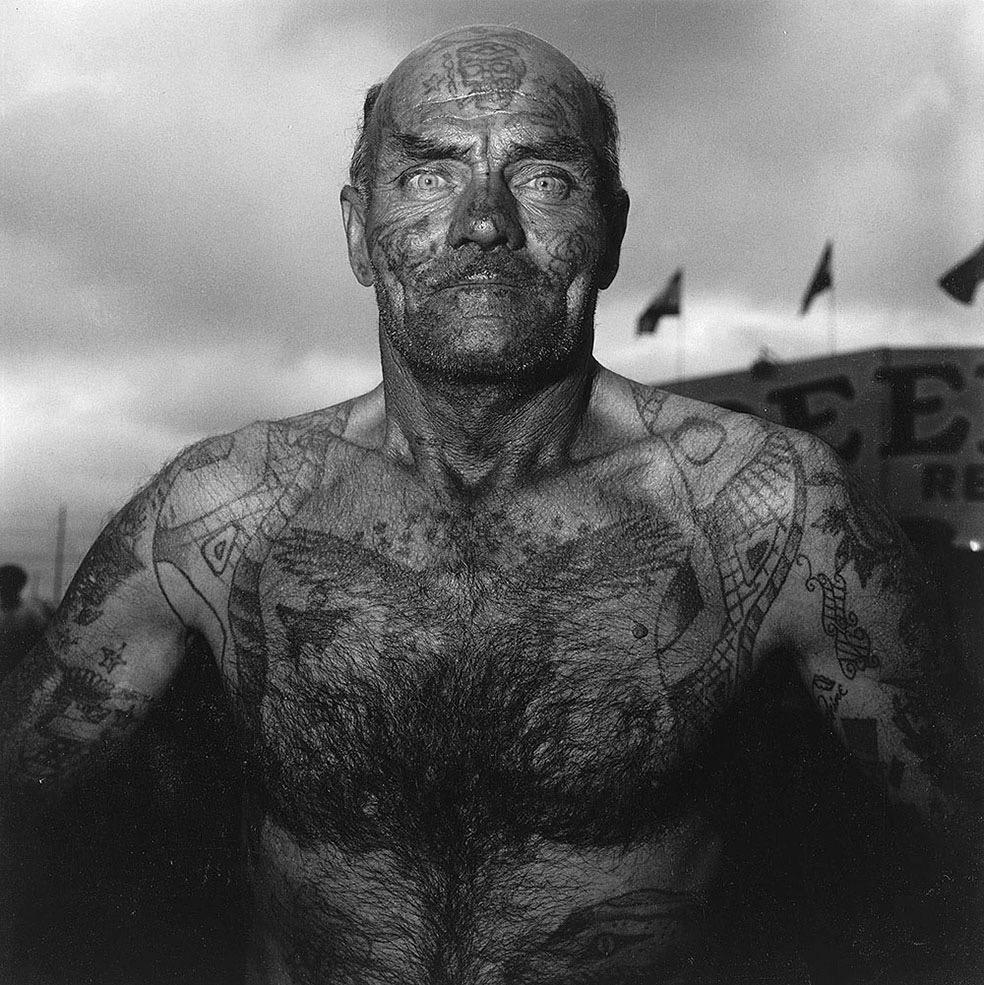

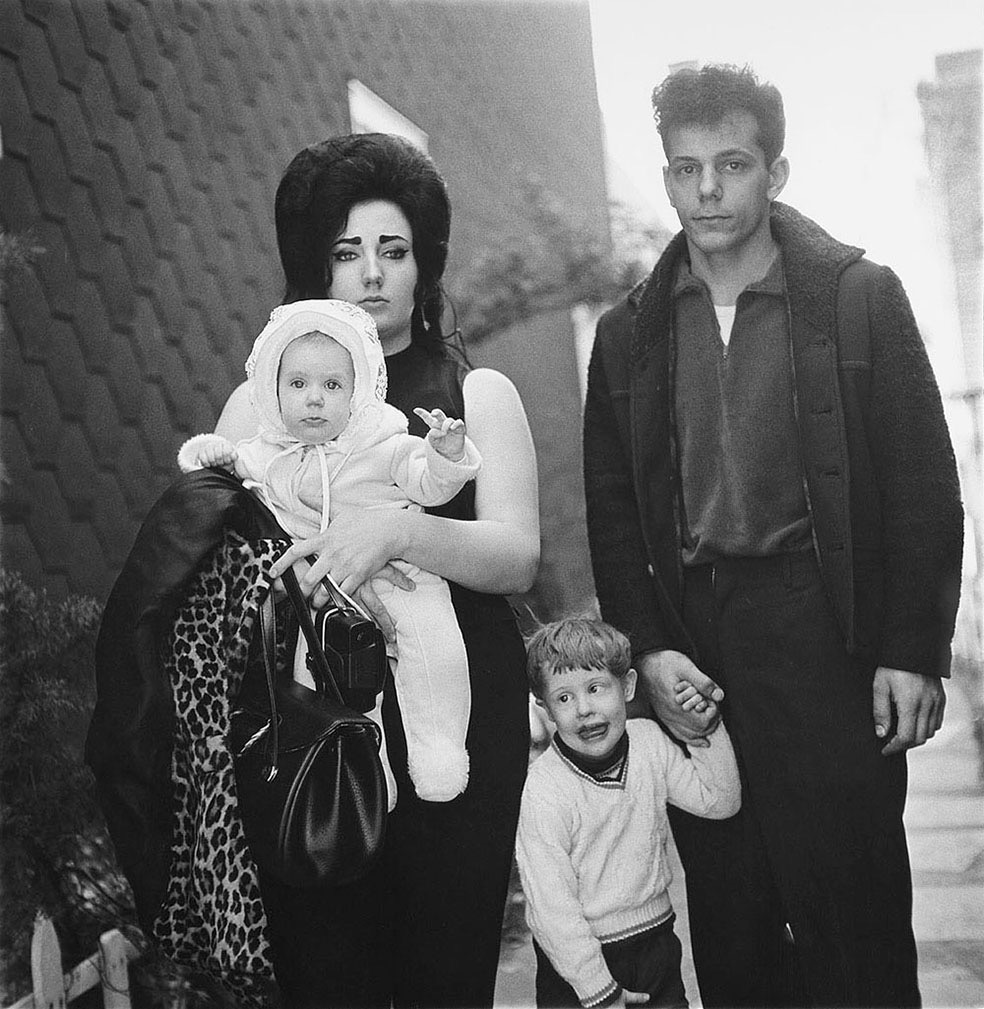

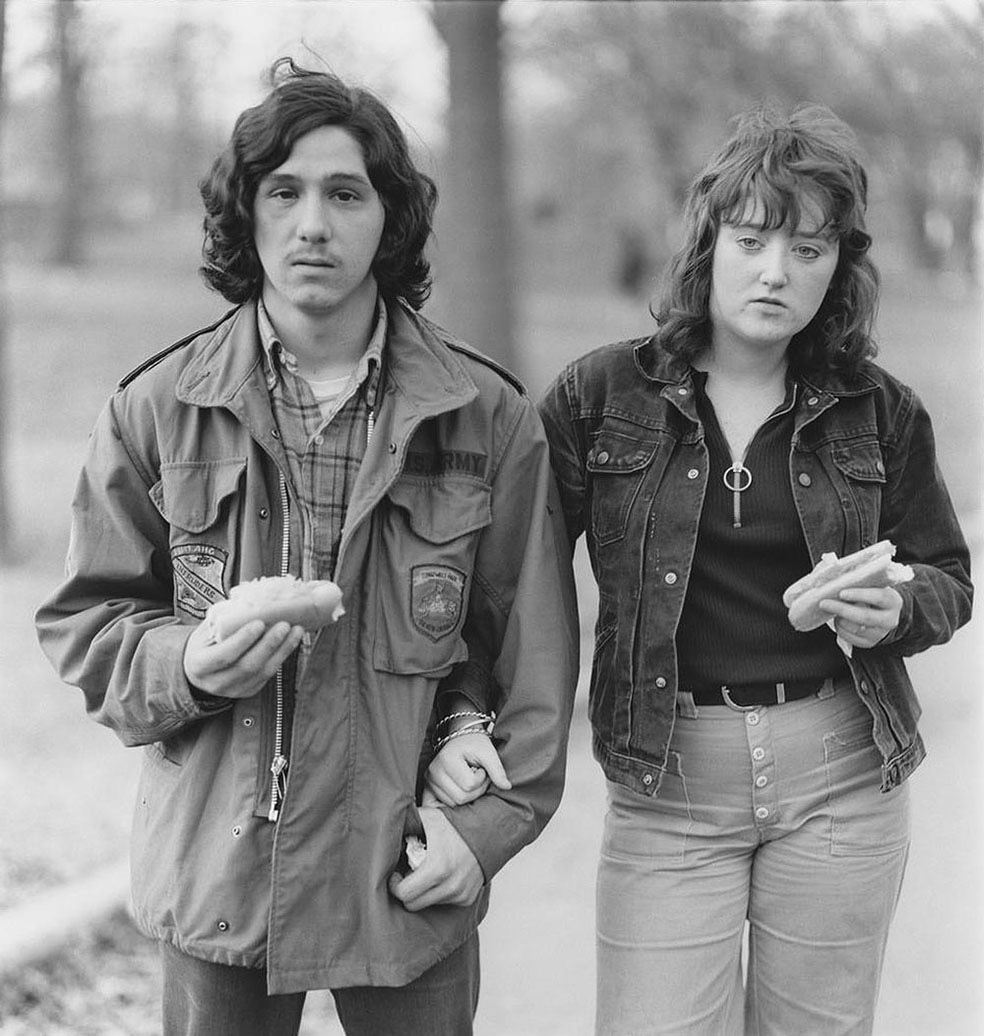

Diane Arbus (March 14, 1923 – July 26, 1971) was an American photographer noted for photographs of marginalized people—dwarfs, giants, transgender people, nudists, circus performers—and others whose normality was perceived by the general populace as ugly or surreal. Her work has been described as consisting of formal manipulation characterized by blatant sensationalism.

In 1972, a year after she committed suicide (there exists a popular cliche of her being the Sylvia Plath of photographers), Arbus became the first American photographer to have photographs displayed at the Venice Biennale. Millions viewed traveling exhibitions of her work in 1972–1979. The book accompanying the exhibition, Diane Arbus: An Aperture Monograph, edited by Doon Arbus and Marvin Israel and first published in 1972 was still in print by 2006, having become the best selling photography monograph ever. Between 2003 and 2006, Arbus and her work were the subjects of another major traveling exhibition, Diane Arbus Revelations. In 2006, the motion picture Fur, starring Nicole Kidman as Arbus, presented a fictional version of her life story.

The Arbuses’ interests in photography led them, in 1941, to visit the gallery of Alfred Stieglitz, and learn about the photographers Mathew Brady, Timothy O’Sullivan, Paul Strand, Bill Brandt, and Eugène Atget. In the early 1940s, Diane’s father employed them to take photographs for the department store’s advertisements. Allan was a photographer for the U.S. Army Signal Corps in World War Two.

© Diane Arbus

In 1946, after the war, the Arbuses began a commercial photography business called “Diane & Allan Arbus”, with Diane as art director and Allan as the photographer. Diane would come up with the concepts for their shoots and then take care of the models. She grew dissatisfied with this role, a role even her husband thought was “demeaning.” They contributed to Glamour, Seventeen, Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar, and other magazines even though “they both hated the fashion world”. Despite over 200 pages of their fashion editorial in Glamour, and over 80 pages in Vogue, the Arbuses’ fashion photography has been described as of “middling quality”. Edward Steichen’s noted 1955 photography exhibition, The Family of Man, did include a photograph by the Arbuses of a father and son reading a newspaper.

In 1956, Arbus quit the commercial photography business. During a spring shoot for Vogue, Arbus came to the realization that she didn’t want to do it anymore. It is noted that she simply stated, “I can’t do it anymore. I’m not going to do it anymore.” She began wandering the streets of New York City with a 35mm Nikon. She would follow strangers and wait in doorways until she saw someone she felt compelled to photograph. She would number her film as she developed her photos. Her last known negative was labeled.

Although earlier she had studied photography with Berenice Abbott, her studies with Lisette Model, which began in 1956 with her enrollment in one of Model’s classes taught at The New School, led to Arbus’s most well-known methods and style. She began photographing on assignment for magazines such as Esquire, Harper’s Bazaar, and The Sunday Times Magazine in 1959. Around 1962, Arbus switched from a 35 mm Nikon camera which produced grainy rectangular images to a twin-lens reflex Rolleiflex camera which produced more detailed square images, on larger 2 1/4 film.

In 1963, Arbus was awarded a Guggenheim Fellowship for a project on “American rites, manners, and customs”; the fellowship was renewed in 1966. In 1964, Arbus began using a twin-lens reflex Mamiya camera with flash in addition to the Rolleiflex. Her methods included establishing a strong personal relationship with her subjects and re-photographing some of them over many years. During the 1960s, she was hired by The Matthaeis’ (art collectors) to photograph them while she also taught photography at the Parsons School of Design and the Cooper Union in New York City, and the Rhode Island School of Design in Providence, Rhode Island.

The first major exhibition of her photographs occurred at the Museum of Modern Art in an influential 1967 show called “New Documents”, alongside the work of Garry Winogrand and Lee Friedlander, curated by John Szarkowski. Szarkowski presented what he described as “a new generation of documentary photographers”, described elsewhere as “photography that emphasized the pathos and conflicts of modern life presented without editorializing or sentimentalizing but with a critical, observant eye.”

© Diane Arbus

Some of her artistic work was done on assignment. Although she continued to photograph on assignment (e.g., in 1968 she shot documentary photographs of poor sharecroppers in rural South Carolina for Esquire magazine), in general her magazine assignments decreased as her fame as an artist increased. Szarkowski hired Arbus in 1970 to research an exhibition on photojournalism called “From the Picture Press”; it included many photographs by Weegee whose work Arbus admired.

Using softer light than in her previous photography, she took a series of photographs in her later years of people with intellectual disability showing a range of emotions.At first, Arbus considered these photographs to be “lyric and tender and pretty”, but by June, 1971, she told Lisette Model that she hated them.

Among other photographers and artists she befriended during her career, Arbus was close to photographer Richard Avedon; he was approximately the same age, his family had also run a Fifth Avenue department store, and many of his photographs were also characterized as detailed frontal poses. Another good friend was Marvin Israel, an artist, graphic designer, and art director whom Arbus met in 1959.

During her career, Arbus photographed Mae West, Ozzie and Harriet Nelson, Bennet Cerf, famous atheist Madalyn Murray, and Marguerite Oswald (Lee Harvey Oswald’s mother).

Her photography style is said to be “direct and unadorned, a frontal portrait centered in a square format. Her pioneering use of flash in daylight isolated the subjects from the background, which contributed to the photos’ surreal quality.”

© Diane Arbus

© Diane Arbus

© Diane Arbus

© Diane Arbus

© Diane Arbus

© Diane Arbus

© Diane Arbus

© Diane Arbus

© Diane Arbus